Home » Posts tagged 'composition'

Tag Archives: composition

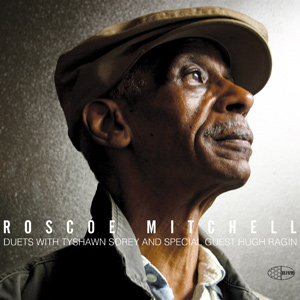

Time Pressures: Short Take on Roscoe Mitchell with Tyshawn Sorey and Hugh Ragin

April 12, 2013 4:48 am / Leave a comment

Short Take on Nicole Mitchell, Solo

March 28, 2013 2:27 am / Leave a comment

I spent the day yesterday off and on with Nicole Mitchell‘s remarkable new cd on my player. Engraved in the Wind, released on the French Rogueart label, is a set of compositions and improvisations for solo flute (with a track or two overdubbed, but most cuts using a single live instrument). Nicole Mitchell has worked in a number of musical contexts, from collaborative ensembles and AACM repertory groups to her own Black Earth Ensembles, but here she is in many ways at her most vulnerable — and also, her most moving. This album doesn’t merely showcase her virtuosity, which is thoroughly impressive; she is hands down and unquestionably one of the most accomplished and brilliant flautists in the world, working now in any idiom or sub genre, from classical to jazz and beyond. Mitchell’s huge instrumental technique, whether focused on fundamentals or developing an extended sonic palette, inevitably serves the musical demands of a given moment. The disc intermingles commissions from colleagues (and one piece from the emerging contemporary repertoire for solo flute, Alvin Singleton‘s “Agoru III”) with a series of improvisational explorations of various elements in Mitchell’s instrumental language, a concept akin to Anthony Braxton‘s For Alto, although Mitchell’s rhythmic and harmonic senses are entirely her own; her playing sounds little to nothing like Braxton’s, and she prefers (to my ears, at least) a more folk-based and lyrical melodic tactic. There is a debt here, perhaps, to James Newton‘s Axum, and Newton is one of the composers to offer an original composition, in this instance “Six Wings,” for Mitchell’s recital. But while she often acknowledges her indebtedness to traditions of Afrological music-making — “Great Black Music, Ancient to the Future” — her voice, at this point in her career, has become fully her own. (Joe Morris provides excellent liner notes that speak to her technique and to her musical approaches much more eloquently than I can here.) On the album, she explores a wide range of textures and timbres, but my favourite cut so far is “Dadwee,” a folksy (even blues-ish) line co-composed with Aaya Samaa that demonstrates the almost buttery richness and harmonic density of her flute tone. Her music nourishes as it unfolds. The recording, done at UC Irvine, is intimate and full, very present, which helps, of course. But what most impresses me, as I listen, is the warmth and closeness of her music. Nicole Mitchell has created a definitive album of solo flute music, one to which I am sure I will return again and again.