Home » Posts tagged 'improvisation' (Page 6)

Tag Archives: improvisation

Evan Parker Live at the Western Front

March 24, 2013 12:43 am / Leave a comment

Short Take on Tim Daisy & Ken Vandermark

February 24, 2013 1:26 am / Leave a comment

Found a copy last week of Light on the Wall, a double LP by Tim Daisy (percussion) and Ken Vandermark (reeds), recorded as a duo and both solo in Poland in May 2008, and issued on Laurence Family Records. The sound, both live and in the studio, is excellent. You can really hear Daisy’s distinctively open sense of space in the live duo set; Vandermark offers a set of solo “Etudes for Jimmy Giuffre,” but to me their duos not so much build on Giuffre’s chamber-ish conceptions, as recall duos by another Jimmy, Jimmy Lyons, with Andrew Cyrille–not that there is anything derivative in this music, but rather that both are thoroughly cognizant of their position in an emergent sense of a building tradition of forward-thinking sonic experimentation, the extemporaneous edge where the performing present takes up its audible pasts: a historicity of the avant-garde, coming on. That, and it’s a great record.

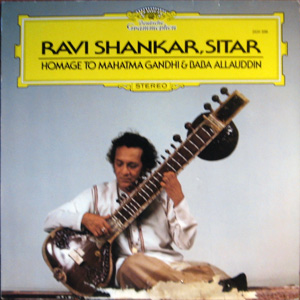

Brief Prose Alap, Remembering Ravi Shankar

December 21, 2012 8:01 am / Leave a comment

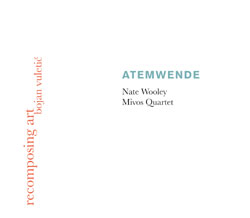

Breathturn

December 12, 2012 9:51 pm / Leave a comment

Lip Shake

October 2, 2011 8:27 pm / Leave a comment

“Lip Shake” is a brief piece composed for and during a master class with Dave Douglas at U. B. C., on 22 September 2011. Dave Douglas was in town working on a commission for the Turning Point Ensemble. The master class was a hands-on discussion of composition, during which Dave had everyone present — mostly music students and academics — write a composition for the available instruments, a trumpet and a trombone, with trap percussion, in about 9 minutes. I tried some notated music, but quickly realized I had no ear for sight-reading or sight-writing at all, so I wrote some words on the supplied manuscript paper instead. The poem, which I think of as a score for saying words through a solo trumpet, was revised from this draft later. (A reproduction of this draft can be seen in this post, below; the finished poem-score can be found by clicking on the title link above. You can see if you squint hard at the image how it was originally intended as a duo for two horns, but I don’t think the counterpoint worked, and I also like the idea of the solitary voice as horn and as sort of cracked a little, as inherently not quite itself.) Needless to say, I found I was a bit shy about offering it up to be played at the session. Despite the encouragement to experiment, there seemed to be a real expectation both from Dave Douglas and from the attendees for conventional notation and performance styles; by conventional, I mean generic, I think. We were certainly encouraged to think a little bit outside of our cognitive boxes. What I saying isn’t a complaint about the class. I was an interloper there, and really didn’t want to stand out in any way, or be thought of as intruding. I find I can learn a lot about word music, melopoeia, by paying attention to musicians and composers, particularly around texture and rhythm. And particularly musicians and musical thinkers of this very high calibre. I’m really grateful to have been able to attend the class, and to hear a little bit about how those present thought about sound, both theoretically but — really more pertinently — practically. The idea, for instance, of rhythmic duration, of a beat having extension rather than being some kind of singularity, I find fascinating.

The class was great, very useful. Dave didn’t do a lot of lecturing, but encouraged feedback — not just from him but from everyone there — on the material that had been instantaneously composed and played. He even produced his own on-the-spot composition, for which he invited feedback, as if he too were a nearly-equal particpant in the various compositional processes unfolding around him. The point was, he said, to try to really write what you’re hearing in your head. In music, as he put it, “you can’t outrun who you are.” He quoted something he’s heard from Anthony Wilson: that composing is “the process of transcribing a melody that already exists in your mind.”

For me, in some ways, treating the poem as score means both something linked to this idea of noetic transcription — getting your mind onto the paper — and something opposed to it: opening the page up to the unruly aspects of imaginary performance, leaving space amid and even within the phonemes and dipthongs for alternatives to sound. Potentiality as typographic space, as leading.

This score is called “lip shake” because Dave Douglas mentioned different kinds of trumpet sounds during the class, and that one stood out, and because making the phonemes sound down the brass tubing is going to involve particular kinds of manipulating of your lips, tongue, teeth, windpipe, embouchure, against the mouthpiece. If, that is, you decide to perform it that way.